Oxplore Book Club started in March 2021. Since then we have published new resources on a range of different texts. Keep scrolling to rediscover some of our favourite bits of Book Club, and click here to find our supporting worksheets.

Let's look back...

The journey to finding yourself

Written by C. S. Bhagya

Through their poetry, Moniza Alvi, Caleb Femi, and Mary Jean Chan share their experiences of growing up in Britain. While they each draw from different cultural heritages—Pakistani, Nigerian, and Chinese respectively—their poetry speaks of the variety of identities that make up the UK. They each skillfully present how difficult it is to think of belonging and identity in just one way.

The Sari by Moniza Alvia

Alvi’s poem, 'The Sari' demonstrates the uncertainty of identity that has marked her own personal experience. Namely, growing up in a part of England, which “didn’t seem very multi-cultural in the nineteen fifties and sixties". (source)

In this poem, she fantasises about what it might have been like to be raised in Pakistan. Something that stands out is the contrast (juxtaposition) between the number of different people in the Pakistani context and the sole English grandmother who takes a telescope to gaze “across continents” (i.e. Europe and Asia). The distance between the two continents is showcased here as a difference of community. The sense of being surrounded by a community of close ones seems emphasised in the Pakistani context. However, this sense is challenged in the next stanza where a connection is established between Lahore, Hyderabad, “across the Arabian Sea,” and seemingly also to Britain from where her English grandmother peers.

Image credit: Baljit Johal via Pexels.

The sari becomes a motif (reoccurring idea or symbol) of cross-cultural connection. Helped by its flowing and flexible shape, it becomes a metaphor for Alvi’s ever-changing self which finds itself fluttering between different cultures.

Alvi seems to imply in the poem’s final lines, that it’s possible for your identity to be rooted in your body rather than any specific part of the world: “Your body is your country”. Plus, it’s the love and understanding of Alvi’s family—her father, Grandmother etc —that allows her to think about herself both through her family and as an individual.

Caleb Femi’s poetry

The themes of travel and belonging to multiple places at once that we encounter in ‘The Sari’ are repeated in Caleb Femi’s poem, 'A Tale of Modern Britain', commissioned by Heathrow Airport. In a filmed version (see below), Femi performs the poem whilst video footage of people moving through the airport (arriving, departing, and greeting loved ones in intimate moments) plays. These actual journeys symbolised by travellers at the airport provide the substance of Femi’s ideas about how the self is made and unmade by movement. Femi describes the emotional impact of travelling: “You arrive at the end of the horizon/ standing at the tarmac mouth of home/ lighter if you left it all behind – heavier if you brought it all with you”.

The video demonstrates how different multimedia (visuals, music etc) can interact to bring a poetry performance to life. Femi’s poem also offers insightful commentary about the different identities that form “this marketplace of modern British culture.” He even includes some amusing references to a few stereotypes associated with British identity: “We’re not all about tea and crumpets – well some of us are.”

Similar to how the sari becomes a physical object that allows new ways to imagine the self and belonging in Alvi’s poem, the airport terminal performs the same function in Femi’s performance. Femi asks listeners to “Imagine a terminal as a portal to a new version of yourself,” showing how the airport becomes a place not just to mark physical journeys, but also a door to new worlds of the self.

The “runway tarmac of Heathrow airport” reappears in another poem about identity and familial belonging titled 'My Father’s Son' (see video above). The room where Femi waited to get a phone call from his father, who had left Nigeria and flown to London, smells of the airport to Femi. He describes his father’s voice as booming like the thunderstorms that disrupted playtime at school -- demonstrating the power of the voice in Femi’s consciousness at a very young age.

At the end of the poem, Femi imagines seeing himself in puddles and associates his self as an offshoot of his father. Here Femi is formed in his father’s image; or rather, he sees himself as giving shape to the power of his father’s voice.

Mary Jean Chan’s poetry

The theme of family also features in Mary Jean Chan’s work, where she repeatedly imagines her selfhood and identity through her relationship with her parents, particularly her mother. In the poem 'Names', Chan talks about the difficulty of talking about her queer identity and gaining acceptance from family. The challenges of maintaining tense relationships is highlighted further in the poem entitled: 'The mother finds her own wild, lost beginnings deep within the body of her daughter'*. The title of the poem and much of its imagery implies that the relationship between the mother and daughter in the poem shape each other. Their relationship is not always ideal, and often messy and painful.

This poem is highly intertextual as it draws on the work of the theorist and academic Jacqueline Rose and the Chinese-American poet Chen Chen. Chan’s poem is, in many ways, a response to a line from Chen Chen’s poem 'Poplar Street': “Sometimes, parents and children become the most common of strangers. Eventually, a street appears where they can meet again.” Through this line, and the motif of the street, Chan imagines the daughter in the poem reconnecting with her estranged parent through her “acumen for/ language.” Her poem is similar to Femi’s in thinking of the daughter as “born/ into the slip-/stream of your mother’s unconscious.” The image of the slipstream (a current of air behind a quickly moving object) helps to think about the mother as a person who has a lot of power to determine the kind of person the daughter will eventually become. The daughter benefits from the possibilities generated by the mother’s personality and life, but at the same time, can be a stranger to the older generation’s thinking and habits. In this context, the street, like the terminal in Femi’s poem, and the sari in Alvi’s, becomes a symbol of hope. Chan notes: “I wrote/ to find/ the street/ where we/ might meet/ again.”

This brief analysis of these three poets’ work highlights questions about how family relationships and intergenerational similarities and differences can take centre-stage in poetic form. The poets frequently use the imagery of travelling and streets to think about how the journey to understanding yourself is not an easy one. In their poems, they trace how it is frequently marked by difficulties, uncertainty, interruptions and pain, as much as by joy.

*This poem was published with the Academy of American Poets as part of the "Poem-a-Day" series.

C. S. Bhagya is a DPhil candidate in English at Merton College, University of Oxford. She has MA and MPhil degrees in English from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her doctoral dissertation is on “Tropes of Exception: Representations of the Emergency in Indian Writings in English.” Her academic writing has appeared in the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, Oxford Research in English, Queen’s Political Review, and the open educational resource hub Writers Make Worlds.

C. S. Bhagya is a DPhil candidate in English at Merton College, University of Oxford. She has MA and MPhil degrees in English from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her doctoral dissertation is on “Tropes of Exception: Representations of the Emergency in Indian Writings in English.” Her academic writing has appeared in the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, Oxford Research in English, Queen’s Political Review, and the open educational resource hub Writers Make Worlds.

What is performance poetry?

Oxford student and poet, Hannah Ledlie shares what performance poetry means to her. She also gives her take on a long-standing debate in poetry known as 'stage versus page'.

Let's delve back into the worlds of science-fiction and dystopian literature...

Let's delve back into the worlds of science-fiction and dystopian literature...

When did science fiction begin?

According to Chelsea, this is a complex question, and the answer depends on how we define science fiction. If we include utopian fiction (stories which imagine ideal worlds) within the genre, then you could argue that science fiction began centuries ago. Thomas More’s 'Utopia' – the first utopian novel – was written way back in 1516.

But science fiction as we think of it today (advanced technology! space exploration! aliens!) is a more recent occurrence. It’s difficult to pinpoint a single example of the first traditional science fiction story, but Chelsea points to 'Frankenstein' by Mary Shelley (1818) and the 'Time Machine' by H. G. Wells (1895) as important early works.

The popularisation of science fiction

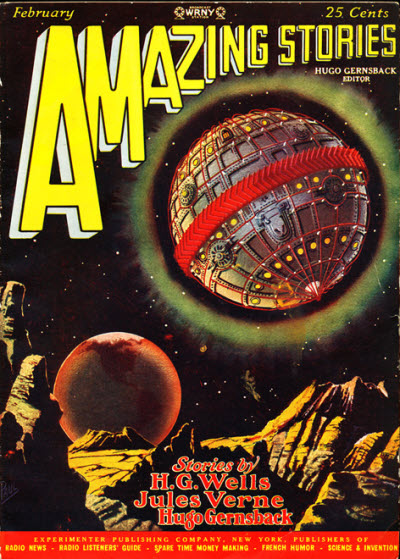

Chelsea explains that many people believe science fiction was first popularised by a man called Hugo Gernsback, who ran the magazines, ‘Amazing Stories’ and 'Wonder Stories', in the 1920s and 30s.

Image credit: Frank R. Paul / Experimenter Publishing via Wikipedia. Public Domain.

‘Gernsback considered the work that he was published ‘science fictional’, and the idea was that his stories contained an element of science taken to the extreme.’

The genre grew in popularity in the decades that followed with John W Campbell (editor of the magazine 'Astounding Stories') seen as another influential figure in this movement.

In the 1960s and 70s, a noticeable difference emerged between American and British science fiction. ‘In the States, there was quite a lot of positive science fiction, which saw future technological developments in a very positive light. There was the idea that they would bring peace and prosperity whereas British science fiction was quite pessimistic (believing the worst will happen)!’

Is science fiction always political?

Science fiction allows us to imagine amazing (utopian) futures. But it also gives us a chance to explore alternative systems of government and consider the dangers of authoritarianism (very controlling systems of power). Stories describing imagined communities or societies which are dehumanizing, undesirable and frightening form part of what's known as dystopian fiction.

Some science fiction theorists, such as Darko Suvin, believe that all science fiction is part of a broader political project. Others, such as Samuel R. Delany, believe in ‘art for art’s sake’, and think that science fiction is valuable in its own right.

Do you think all science fiction is political?

Speculative fiction

When learning about science fiction, you may have also come across the term ‘speculative fiction’. What is it, and where does it come from?

‘Speculative worlds are worlds that we recognise but are different in one or two particular ways. The term works quite nicely as it also includes fantasy.’

Chelsea explains that the term is relatively new, and it became popularised after a public disagreement between two science fiction writers. In 2003, Margaret Atwood (pictured below) distanced herself from sci-fi, explaining that she preferred to describe her work as ‘speculative fiction'.

Image credit: Mark Hill Photography via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

‘This statement caused an uproar in fan and writing communities. Author, Ursula Le Guin then reviewed one of Atwood’s books and said that she was trying to avoid being ‘shoved into the literary ghetto by the literary bigots.’ Le Guin’s position was that Atwood was trying to make her work stay viable (successful) in the literary marketplace.’

In other words, some people believe that ‘speculative fiction’ is a term used by writers who want to make their work appear more serious. As Chelsea says, ‘the term speculative fiction tries to rehabilitate the genre.’ Meanwhile, some think it is a useful term because it is more inclusive of fantasy works.

The decline in serialised science fiction

Towards the turn of the century, magazines and serialised science fiction declined in popularity.

‘We don’t tend to read magazines for fiction anymore, but for the longest time, that was how you got stories. Nowadays, there are some magazines which do relatively well, but they are largely read by fans and contributors. They’re less considered popular reading. And so science fiction has suffered quite badly, I think, from that origin story of being popular rather than highbrow.’

Do science fiction writers use real science in their work?

In order to build believable worlds and plots, science fiction writers often make use of existing real-world science. Chelsea explains that award-winning sci-fi writer Ken Liu often explores alternative energy in his stories.

‘He actually built the machines to see if they would work. He also developed some of the code which he then writes about in his books.’

Sometimes though, science fiction deals with topics so fantastical that we cannot say whether or not they are possible.

‘And that’s one of those moments when you start thinking what is genre and why does it matter and why are we pigeon-holing texts?’ says Chelsea. ‘Which is where speculative fiction becomes a useful term.’

Have imaginary inventions or predictions from science fiction ever come true?

The short answer is yes!

‘A great example is The Time Machine by H. G. Wells. Published in 1895, the main character has a dinner party and presents this mad idea to his guests. He’s like, ‘we work on the three-dimensional plane, and there’s a fourth dimension: time.’ That was ten years before Albert Einstein comes up with his theory of relativity. That’s a clear example of literature preceding science. More recently, if you watch Star Trek, you can see they’ve got big tablets, so that’s like the forerunner to the iPad!’

Science fiction in the future

Recently, there have been lots of advancements in technology and space exploration. In March 2021, NASA’s Perseverance Rover landed on Mars. Meanwhile, Elon Musk’s company SpaceX hopes to take humans to the planet by 2026.

It will be interesting to see how these developments in real-world science influence science fiction. Will they lead to more dystopian or more utopian stories?

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS. Public Domain.

‘There is a lot of pessimism in science fiction about future slave communities. Almost all science fiction imagines that we’re going to enslave someone. Ourselves, aliens, AI robots… someone’s going to have a bad time. But the way the upper classes will live is also always imagined as being utopian.’

Why does science fiction continue to be a popular genre?

Science fiction stories allow us to think about how our lives might change, and what potential threats we might face.

‘What it all comes down to, is science fiction stories are often fun, they appeal to a sense of adventure, and they allow for an exploration of socio-political problems. What a genre, to be able to deal with all of those things at once and package them in a way that really engages your imagination!’

Let's learn more about magical realism

Let's learn more about magical realism...

Magical Realism exists when elements of magic are interwoven into the real world. It shares similarities with fantasy and science fiction, but the main difference is the fact that the world that the author constructs is entirely familiar to us – there is no planet Zog! Most characters are human, and you are invited to suspend disbelief and immerse yourself in the narrative. It often blends the mundane with the extraordinary, blurring the lines between reality and imagination.

Origins of Magical Realism

The term was first used by the German art critic Franz Roh in his book Nach-Expressionismus: Magischer Realismus in 1925, though it didn’t become popular until the 1960s. The literary movement has its roots in Latin and South America where Magical Realism was embraced as a way to create a unique literary voice that blended the traditions and legends of the region with modern storytelling techniques. It is also thought that the genre was popular thanks to the political turmoil of the Cold War and the Cuban Revolution as it provided both a method of escapism, but also a way to comment on injustices.

Magical Realism is now synonymous with the Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez who wrote one of the most significant works that popularised the genre, One Hundred Years of Solitude. The novel tells the story of the Buendia family, who live in the strange and mystical town of Macondo. Some other famous examples include Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie and Toni Morrison’s famous novel Beloved, where her protagonist is haunted by a vengeful ghost. Can you name any other classic examples of the genre?

Popularisation of the genre

Fantasy has always been a popular genre within Young Adult fiction, but we are seeing more and more Magical Realism novels popping up. That said, there are some classic examples such as the Harry Potter series where magic and the real world exist, not necessarily harmoniously, together. Platform 9 ¾ is magical, but Kings Cross is not (as anyone who has experienced a crowded or a delayed train can attest to!). Other popular titles include the Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children series by Ransom Riggs features a magical school for children with unique abilities. The Mortal Instruments series by Cassandra Clare has magical creatures living in the human world.

Here are some possible reasons as to why Magical Realism is so popular:

- It provides an escape from reality: Magical Realism allows readers to enter a world that is beyond the mundane and ordinary. It can be a way to break away from the stress of everyday life and immerse oneself in a magical and mystical world.

- It blurs boundaries between reality and fantasy: The blending of the real and the magical can make for a unique reading experience. The simultaneous presence of the two elements can also challenge the reader's idea of what is real and what is not.

- It offers a fresh perspective: This genre often tackles social, political, and cultural issues through the guise of magical or supernatural elements. It can provide a new perspective on familiar topics or issues.

- It allows for creativity: The genre of Magical Realism allows writers to insert surreal or magical elements into seemingly normal and everyday situations and play with the reader's perception of reality.

- It emphasises the importance of storytelling: Magical Realism has been linked to oral storytelling traditions, where magical or supernatural elements are often used to teach moral lessons or convey wisdom. This helps to connect readers to the historical and cultural roots of storytelling.

What techniques do writers use to make the magical seem plausible in an everyday setting?

Magical Realism is a difficult genre to define because it can take many forms. However, writers use various techniques to make the stories seem plausible. They often use a straightforward and matter-of-fact writing style, even while describing strange or supernatural events. The narrative voice can vary from the first-person to a more omniscient narrator, shifting between different perspectives.

Another way writers create plausibility is by grounding the stories in familiar settings, such as villages or small towns. They often incorporate regional myths and stories into the plot, blending them with modern-day situations. This technique connects readers with the story on a personal level, making it easier for them to accept the magical elements. Do you know any stories or myths that might make for an interesting adaptation into a Magical Realism novel?

The future of the genre

The future of Magical Realism will depend on how authors continue to incorporate it into their storytelling. With the rise of technology, authors may have to find new ways to integrate magical elements while keeping them believable and relevant to modern society. It's possible that magical realism will evolve to become more intertwined with technology itself, creating new and innovative blends of fiction and reality.

Introducing 'The Girl of Ink and Stars'

Kiran Millwood Hargrave shares some of her thinking behind 'The Girl of Ink and Stars' and reads aloud some of the text.

The story

Frances Hardinge’s A Skinful of Shadows, published in 2017, tells the story of twelve-year-old Makepeace Fellmotte, a young girl born with the ability to absorb and serve as a living host for the spirits of the dead. The novel is set shortly before and during the First English Civil War (1642-46) in several locations: Poplar, a mostly Puritan village in the vicinity of London; Grizehayes, the ancestral home of Makepeace’s father’s family; and Oxford. Steeped in historical detail, the book skilfully blends the historical context of the Civil War with Makepeace’s complex experience of her paranormal powers.

The narrative immediately foregrounds Makepeace’s feelings of unbelonging, her uncomfortable suspicion that her role in the Puritan community of Poplar is, as her name suggests, merely that of being an “offering” of peace-making extended to the town’s “godly folk.” Makepeace’s and her mother’s anxiety to be accepted by the pious village community acquires further significance in light of certain mysterious facts that seem to characterise Makepeace’s life, like her recurrent nightmares full of demons and evil spirits. As readers, we are immediately sympathetic with Makepeace’s feelings of exclusion (which will accompany her throughout the book, even as her circumstances change), but also hooked on the mystery of her involvement with the world of the occult.

“For a little while she could believe that Mother and Makepeace were part of something bigger, something wondrous alongside all their neighbours. The feeling never lasted.”

Treacherous voices

Tragedy strikes Makepeace’s life during a trip to London, when she and her mother become involved in a riot between Parliamentarians and Royalists, the two factions who fought in the First English Civil War. Not only does Hardinge, throughout the novel, include many historical references that flesh out the setting, but she also invites her readers to discover this period of English history through the eyes of her protagonist, by showing how young Makepeace understands the complex forces at play during the Civil War. In Poplar, for example, Makepeace learns (and believes) that King Charles is turning away from Parliament because encouraged by his “evil advisers,” who seek to turn the King into a tyrant, drive him to persecute the loyal and pious Protestants, make him fall for the “devilish Catholic plot” set up by “the Devil himself.” But when she arrives at Grizehayes, she is shocked to hear the members of her father’s family, the Fellmottes, who are aristocrats, talk about the political situation in completely different terms, saying that it’s the Parliament that is trying to rob the King of all his allies.

What is the truth? In the enchanting but also frightening vision of this novel, History itself becomes caught in an unseen, sly web of untraceable influences, each side of the struggle for power trying to take control over reality, much in the same way that evil spirits and ghosts are always ready to take over Makepeace’s mind and body. In such a context, Makepeace’s growth and personal battles also revolve around learning the importance of always listening to the other party, analysing a problem from all angles, and taking the perspective of the Other.

The beauty of speechless things

In the novel’s first chapter, when Makepeace is ten, her mother takes her to an abandoned graveyard chapel, where Makepeace is forced spend the night alone. This will become a regular occurrence in Makepeace life, a training exercise that her mother devises so that Makepeace will learn how to keep the ghosts of the dead out of her mind. Makepeace is terrified, but she also discovers, when she senses the presence of a little mouse sharing the dark and musty chapel with her, that she can find unexpected solace in nonhuman beings, even, and perhaps especially, knowing that these are utterly indifferent to people.

“The mouse was not a friend, of course… But it calmed her to think of it, sheltering from the owls and night-prowling beasts. It didn’t cry, or beg to be spared. It didn’t care if it was unloved. It knew that it could only count on itself. Somewhere, its currant-sized heart was beating with the fierce will to live.”

Later on in the story, following the trail of a “vengeful spirit” that haunts the marshes around her village, Makepeace discovers that the angry ghost belongs to a bear who was brutally tortured and killed by its owners, two travelling entertainers. Makepeace is horrified, furious, and heartbroken, and when the ghost of the bear makes an appearance to attack the men who killed him, Makepeace feels, for the first time, the desire to help one of the spirits that scare her so greatly. She bravely tries to hug the bear-ghost, to keep him from melting away into his own rightful rage. At first, she believes she has failed—but the tenacious Bear will in fact become her closest friend.

What does it mean to empathise with things that have no consciousness or feelings as we humans conceive these words? How is it possible to find comfort in the nonhuman world’s indifference towards us? And what can we discover about ourselves once we let this inanimate world somehow ‘inhabit’ us, like Makepeace does?

Becoming yourself

Makepeace’s coming-of-age story brings her to face her most secret and personal fears, to learn that the difference between an ‘enemy’ and an ‘ally’ is a blurry one at best, and most importantly, to believe in her agency and in the power of expectation—to have the confidence that old systems can be changed as long as there is someone willing to usher change in.

“Perhaps none of the old truths were true any more. This could be a new world entirely, with its own rules…. A world where castles could burn, and kings could die, and no rule was unbreakable.”

In many ways, then, A Skinful of Shadows is as much a book about freedom as it is about the inevitability of our involvement with the world—with history, with the environment, with other people—as Makepeace learns to negotiate between her desire to be free of external influences and her ability, encoded in her very mind, to share herself with the Other.

What do you think? Does Frances Hardinge’s A Skinful of Shadows remind you of any other texts or films you have read/watched that explore similar themes?

Exploring the themes in the novel

Like a Charm (2022) is a magical realist novel set in Edinburgh about a determined, intelligent and powerful girl who is misunderstood – by her parents, by her teachers and, when we first meet her, by herself. The novel explores themes such as good, evil, family, magic and identity. Elle McNicoll leads us through a classic coming-of-age story through which she reveals the importance of having faith in our convictions and our identity.

The story

Ramya Knox has a superpower. Not only is she dyspraxic, which affects her motor skills and processing, but she is also magical![1] Misunderstood by her parents who are frustrated by her clumsiness, Ramya’s grandfather sees something special. He takes the time to treat her with kindness. He believes she is truly intelligent and has supernatural gifts. But her mother, Cassandra, seems to think otherwise and forbids her from seeing him. When he passes away, he leaves Ramya a book which is the key to unlocking her powers! She encounters Sirens, Vampires, Kelpies and other magical beings who both help and hinder her on her journey. This novel explores what it is like to be neurodivergent, the complicated relationships between family members and ultimately what it is like to discover your true self.

The beginning

Elle McNicoll ominously opens the story with a short paragraph lasting only a sentence:

‘the first time I ever saw one of them was the night that I saw my grandfather for the last time.’

We don’t know who or what they are. The author’s tone gives us an indication that whoever these creatures are, they are not to be trusted. We want to know more – there will be more, this was only the ‘first’ time Ramya encounters ‘them’- but McNicoll doesn’t tell us yet. McNicoll is using foreshadowing – where an author hints at future developments while withholding information – to keep us hooked. The way that the author structures the phrase juxtaposes the idea of first and last. This hints at the relationship between ‘them’ and Ramya’s grandfather. We are immediately hooked!

Characterisation

McNicoll’s descriptions, particularly of the characters, are rich and vivid. Ramya is portrayed as observant and wise, but her parents and their friends are depicted as false and insincere. When describing the fickle partygoers in her house at the beginning of the novel, the author writes:

‘people would clink their classes warmly, but their eyes were cool’

McNicoll introduces Ramya’s grandfather as ‘like a fleck of gold underneath the dirt’ (p.2). This simile indicates to the reader how special he is to Ramya and, therefore, the plot. Here, McNicoll uses a technique that she interweaves throughout the novel; in her descriptions she uses juxtaposition, the pairing of contradictory terms (‘warmly, […] cool’; ‘gold underneath the dirt’). As we saw with the opening line, McNicoll’s descriptions are built upon contrasts and the relationships between them. One way to look at her use of juxtaposition is to consider it as a way of the author drawing out more vivid imagery. The other is to think of it as a way of evoking insincerity or duplicity. The world that Ramya thought that she lives in is perhaps not what it seems…

Can you try to find another example of McNicoll using juxtaposition?

Clothes are similarly important to characterisation. For example, when we first meet Aunt Opal, we are told that she had:

‘hair piled high on her head. Dark clothes and dark glasses. Everything about her is dark, apart from the gloves that she’s wearing. They’re bright turquoise. And they only cover the fingers, they don’t stretch all the way up to the wrist.’

Opal’s attire is unusual, which intrigues the reader. Its near-total darkness mimics a shadow, something intangible and something in which anything could be hiding. The reader wants to see the cause of the shadow and what might be hiding in it (peeking out with dashes of bright colour – Opal’s gloves) unmasked. What might the turquoise gloves symbolise? Hope, perhaps?

Where else does McNicoll use clothing to hint at important facets of characters?

Emotions

Ramya’s ability to express emotion evolves over the course of the book. She faces a multitude of difficulties throughout her journey. Initially she is frustrated by her parent’s lack of understanding. The author reveals that her grandparents were the only ones who ever told Ramya she was intelligent, and her parents just got angry at her. How do you feel towards her parents? Ramya certainly is upset by their attitude, and the attitude of her teachers and everyone else for that matter. She doesn’t like to ask for help – she expresses frustration by clenching her jaw.

‘When you’re wired a little differently […] you learn pretty quickly to rely on yourself’

On the one hand, this lends her bravery and determination as she tries to prove everyone wrong. Ramya’s emotions fuel her desire to conquer the evil forces at work. She confronts the Siren, who calls her an ‘emotionally stunted little headcase. Poor academic performer, barely able to hold a pen’ (p.255). She comes out on top partly because of her resilience and bravery, but also because what Ren says is even less true than it ever was: she can express her emotions constructively to other people. Indeed, her ability to keep Ren engaged as she verbally explores how they experience the world and relationships with people totally differently is what saves her cousin. Ramya is able to defy everyone’s expectations and save the day. By the end of the novel, she has built an emotional support system consisting of her friends and family and they are all able to process their feelings and express them in a healthier way.

By the end of the novel, Elle McNicoll gives us an explanation as to why Ramya’s mother, Cassandra, has behaved so cruelly towards her and tried to keep her from encountering magic. She had accidentally set fire to some school toilets and Aunt Opal took the blame. She reveals that:

‘I was too much fire for the world … so I became ice’

We understand why her mother behaved with so much fear towards magic and in the end, we have sympathy for her. It becomes clear that Cassandra has not kept Ramya from the magical world due to intrinsic evil, rather a desire to keep her daughter safe, and to an extent, her own fears. It’s never the facts of her own story or her fears which cause her and Ramya to be emotionally distant. Instead, it is the secrecy which surrounds the past and the fears of the present. As soon as emotions are confronted and shared without recrimination or fear, we (the readers) are left with a sense of relief as the whole family are reconciled. Hopefully it means they’re ready to take on the sirens in the sequel, which comes out in Spring 2023.

What do you think? Does Like a Charm remind you of other books, films or tv shows that explore similar themes?

[1] For more information on dyspraxia see the author’s note about her experiences just before chapter 1.

If you enjoyed the texts we've studied, you may also like...

-

Divergent series by Veronica Roth

-

As both a film series and a series of four novels, the Divergent books are set in a post-apocalyptic world in which society is divided into factions that are determined by people’s abilities. The novel is interesting as a social critique and explores important concerns of maturity, first love and finding one’s true identity.

-

-

The Giver by Lois Lowry

-

Set in a dystopia, 'The Giver' appears at first to be utopian. AS we read on, however, we discover that the speculative element of the novel which is the eradicaton of pain, has lead to a homogenising ‘Sameness’. (Homogenise means to make something similar, usually with regard to a world-view, a group of people, or a society).

-

-

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld

-

Imagine a world where there is no poverty. In Uglies, scarcity is no longer a problem, which seems utopian! However, people have embraced cosmetic surgery whole-heartedly and so on your 16th birthday you become a Pretty through extensive cosmetic surgery, meaning that the world is divided into Uglies and Pretties.

-

-

Metaltown by Kristin Simmons

-

Set in an industrial dystopia, this novel explores three young people’s experiences of a brutally industrialised society that has produced a dog-eat-dog world. The three must learn to understand one another’s different perspectives and together they discover friendship and the meaning of hope.

-

-

The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline

-

In a world where people have lost the ability to dream, only indigenous Native Americans can do so, and as a result, their children are hunted and ‘harvested’ for their bone marrow. The novel follows a group of fugitive teenagers as they attempt to escape this terrible fate and reunite their families. (‘Indigenous’ is a term used to refer to a group of people who lived in a place before colonisers arrived).

-

-

Orleans by Sherri L. Smith

-

This climate apocalypse novel explores how people band together to survive climate catastrophe. A young black woman living in the devastated Delta must try to return a newborn child to her family with the help of an outsider scientist. They must battle climate crises and their own prejudices to overcome and get the child to safety.

-

-

Robot Girl by Malorie Blackman

-

Blackman is a British writer famous for her Noughts & Crosses series. She held the position of Children’s Laureate from 2013 to 2015. The novel ties together cutting-edge futuristic technology and a young girl’s relationship with her father into a fast-paced adventure.

-

-

Refugee Boy by Benjamin Zephaniah

-

The novel tells the story of 14-year-old Alem and the journey he takes travelling to England from Ethiopia. In London, Alem is abandoned by his family in an attempt to protect him from the political issues in his home country. The novel describes the social and emotional challenges he faces.

-

-

Tall Story by Candy Gourlay

-

Gourlay’s novel addresses cross-cultural concerns and body image issues through a poignant story about two siblings, one of whom suffers from gigantism (a rare medical condition causing abnormal growth in children). It is a coming-of-age story about self-love and acceptance.

-

-

Anita and Me by Meera Syal

-

Another coming-of-age story, this novel is set during the 1960s and in the British village of Tollington. Through the eyes of 9-year-old Meena, the novel tracks her growing up years in the predominantly-white communities in the Midlands during the time.

-

-

The Knife of Never Letting Go by Patrick Ness

-

This is the first novel in the 'Chaos Walking' trilogy. Todd lives in a town of only men – and Noise is everywhere. You can hear what everyone thinks and there is no privacy. But somehow something is being hidden from Todd and he has to flee his town, unlearn everything he knows and find answers. You can read the first part of the novel here for free.

-

-

Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

-

In the nation of Panem, the Capitol controls its twelve surrounding districts by making them compete in the Hunger Games. Each year one boy and one girl between the ages of twelve and eighteen must fight to the death on live TV for the enjoyment of the Capitol. Katniss Everdeen volunteers as tribute to protect her sister. But even though her chances are small, she won’t give up without a fight. This book is the first of a trilogy and became super popular through the Hunger Games films.

-