Race plays a big role in our society. But what is it? Is it just our skin colour or something more complex? Some feel we need it to understand events of the past, but it also causes conflict all over the world…

Does race matter?

From the time of early exploration, naturalists (who studied living organisms) and biologists have tried to classify the different human populations they came into contact with as belonging to certain racial groups. This was done according to physical features, which were usually chosen without logical reason.

Phenotype and racial divisions

In biology, physical characteristics are known as phenotypes. Phenotypes are a combination of your genotype – a collection of genes that determine one particular feature – and your environment. So, for example, your weight is a phenotype affected by both your genes and your diet.

Your genes and your environment make you who you are. Image credit: Keith Chan via Wikimedia Commons

Early racial divisions in the 17th-18th centuries were based on physical features (usually skull measurements) linked to geographical region of origin. François Bernier, a French physician, was the first to categorise race this way, in terms that may now seem shocking: "Europeans", "Far Easterners", "Negroes" and "Lapps".

Later, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a German physician and naturalist, invented five racial groups on the basis of skull shape: Mongolian, American, Caucasian, Malay, and Ethiopian. This gave rise to the ideas of monogenism and polygenism, which considered whether the different races all came from a single origin (monogenism) or from different origins (polygenism).

Here his five skulls are labelled (from left to right): Tungusae (Tungus, an indigenous group of Siberian people), Caribaci (from the Carribean islands), Feminae Georgianae (female Georgian), Otaheitae (Tahitian), and Aethiopissae (Ethiopian). Blumenbach used these as examples of his five primary varieties of people: Mongolian, American, Caucasian, Malay, and Ethiopian.

Unfortunately, differences in physical characteristics and supposed differences in character came to be used create racial hierarchies that placed white people at the top. Such hierarchies have been used historically to justify practices such as the slave trade, racial segregation, and the extermination of certain races through eugenics. The Nazis were particularly infamous for this, but were certainly not the only supporters of eugenics and scientific racial hierarchies. The idea that the different races had originated separately, and that some were inferior to others, also made it easy for racism to thrive.

Evolution and our journey out of Africa

In the 19th century, Charles Darwin presented his theory of evolution and concluded that all humans came from a single common ancestor.

Darwin recognised that we are far more similar than we are different. This has been confirmed by modern day genetic analysis. We now know that any human is about 99.5% genetically similar to any other human. Not only that, but people within populations show more genetic variation than those between populations. Sub-Saharan African populations show the greatest genetic diversity, which makes sense when we consider that humans evolved in Africa. Those who migrated out of Africa were smaller populations, and so carried with them only a part of the genetic diversity.

Evolution from a single ancestor has typically been portrayed as a tree, with different groups splitting off at different times through history, followed by no further interaction. Historically scientists believed African people to have split off from the rest of humanity a long time ago, and therefore that they formed a distinct lineage, or “race”.

A more modern way of looking at the evolution of humans is known as the ‘multiregional hypothesis’. This suggests that several waves of expansion out of Africa occurred at different times, and there was gene flow back and forth between populations.

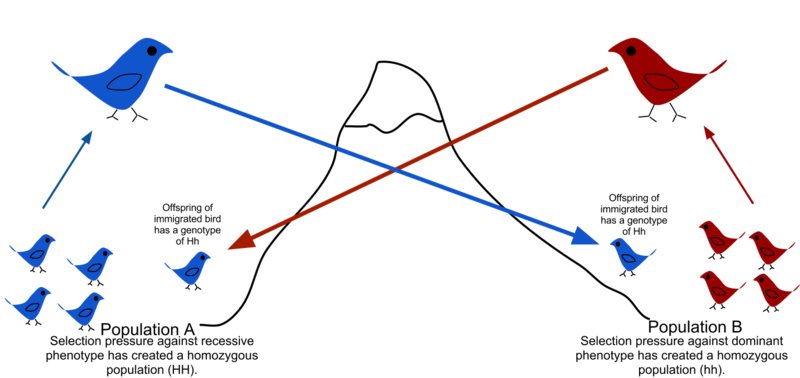

Gene flow, or gene migration, is the transfer of genes from one population to another via immigration of individuals. Take a look at the diagram below:

Image credit: Jessica Krueger via Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: Jessica Krueger via Wikimedia Commons

So what is race, and how is it actually defined?

On a biological level, it is a division lower on the scale than sub-species. All humans belong to the same species and sub-species, Homo sapiens.

A biological race, by definition, is a genetically distinct division, usually across some geographical boundary. That said, because of the very gradual genetic variations across geographical areas (called ‘clinal’ changes), no human “races” fit this definition.

Generally, it's found that people geographically closer to each other are more genetically similar than those geographically distant from one another, but the changes are gradual. So gradual that the more traits you measure and the more human populations you measure, the more categories of human beings you have to make! At one point it was even said that there were up to 65 human races.

There aren’t any single genetic differences between races, where the one race has one variant of a gene and the other has another. In fact, as shown by Craig Venter and his team when they sequenced the human genome, it's possible for a Korean and a white American to be more similar to each other genetically than two white Americans.

What we perceive to be physical racial differences are simply a result of adaptations due to natural selection over thousands of years. The subset of genes to which these differences are due is too small and is not variable enough to be classified as racially distinct. In light of this, there has been a call for the term “race” to be replaced by “ancestry” in the biological literature.

If you want to learn more about this topic, take a look at the short video below created by the BBC and Open University:

Since race has been separated from biology, scientists and philosophers have argued that race is a social construct. A social construct is an idea that is created and accepted by society or a social group. Some important examples include government, laws, and marriage, as well as race and gender. While all these things are socially constructed, they still have a big impact on our daily lives.

Also they're not fixed. Over time, society’s concept of what a government is for, how they should be formed and the power they have, has changed. Likewise, our understanding of race has changed a lot over time.

Does that mean that race isn’t real?

It all depends on how you define 'real'. Race isn’t real in the sense that an apple is real, or a car is real. But there are lots of other social constructs that we would most definitely say are real. The value of money is a social construct, created by society so we could trade goods, and I think we would all agree that money is very real.

Someone’s racial identity is also not fixed. It can change over time as they come to understand themselves differently or as social understandings change. But how people are treated because of how they are racialised (how other people understand their race) also has very real impacts on their lives. Race may be entirely constructed but it is experienced by many people every day.

However, there is a question over whether race is ‘less real’ than things like apples and cars. And if we think it is less real, does that mean it’s less important? Should we stop using the word 'race' altogether?

Writer, Jenée Desmond Harris explores this idea further in the video below:

Why do we need to talk about race?

If biologists aren’t using the term anymore, should we? Here are some of the key arguments for and against this.

Eliminativists argue that we should abandon the concept of race because the term race is historically linked to biological groupings, and there are no such distinct biological groups that match our modern day concept of racial groups.

For example, there are certain genetic markers, such as skin colour, that we use to identify race, but not every person of the same skin colour is part of the same race. Plus, there are people within races that have variation in skin colour. There are lots of other examples of physical traits, such as eye shape and hair texture, that only complicate this further.

However, other philosophers, called race constructivists, say that we should keep the concept of race. They, along with supporters of critical race theory (CRT), believe that racial prejudice is already built into our society.

Society already labels and often discriminates against people according to racial categories. Many scholars and activists argue that we need the term race to recognise this racial discrimination so we can make social and political progress against the racial injustice that is built into many of our social systems. They support race conscious policies that acknowledge racial discrimination in order to address it. We've seen some of the negative effects that systemic, institutionalised racism can have in the recent police brutality cases in America, and the development of the Black Lives Matter movement that followed. To learn about this, take a look in the additional resources at the short documentary, 'Black Lives Matter explained: The history of a movement'.

Unfortunately, these measures have also been controversial. In the United States, republican politicians have tried to ban CRT and similar approaches from being taught in public schools and universities. Eight states (Eight states (Idaho, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Iowa, New Hampshire, Arizona, and South Carolina) have passed legislation to ban it. Twenty more states are attempting to do so. They object to anyone being taught that the US is fundamentally racist or sexist, or that members of a certain race are more inclined to oppress others.

What do you think?

Race and ethnicity – what’s the difference?

Ethnicity is a term much more commonly used by governments, healthcare and in the legal system to identify different groups. Many people believe it's a better term to use as it's less influenced by a history of conflict and segregation. If we were to eliminate our concept of race, ethnicity may be a good substitute as it would still enable us to track social progress and what still needs to change. Employers and other institutions, like universities and schools, use ethnicity data to ensure they are being fair in their recruitment and selection processes, and that people from all backgrounds are given equal opportunities. The biggest difference between race and ethnicity is that it is self-identified. Race is often decided by other people, who might racialise you and treat you differently, but it is up to you which box you tick.

What do you think?

Kofi Annan, Nobel Peace Prize winner and previous Secretary-General of the United Nations, once said: "We may have different religions, different languages, different colored skin, but we all belong to one human race."

Kofi Annan, Nobel Peace Prize winner and previous Secretary-General of the United Nations, once said: "We may have different religions, different languages, different colored skin, but we all belong to one human race."

What's behind racism?

Historian Onyeka Nubia explores why some people are racist - and talks about his own experiences of racism.

Race by numbers

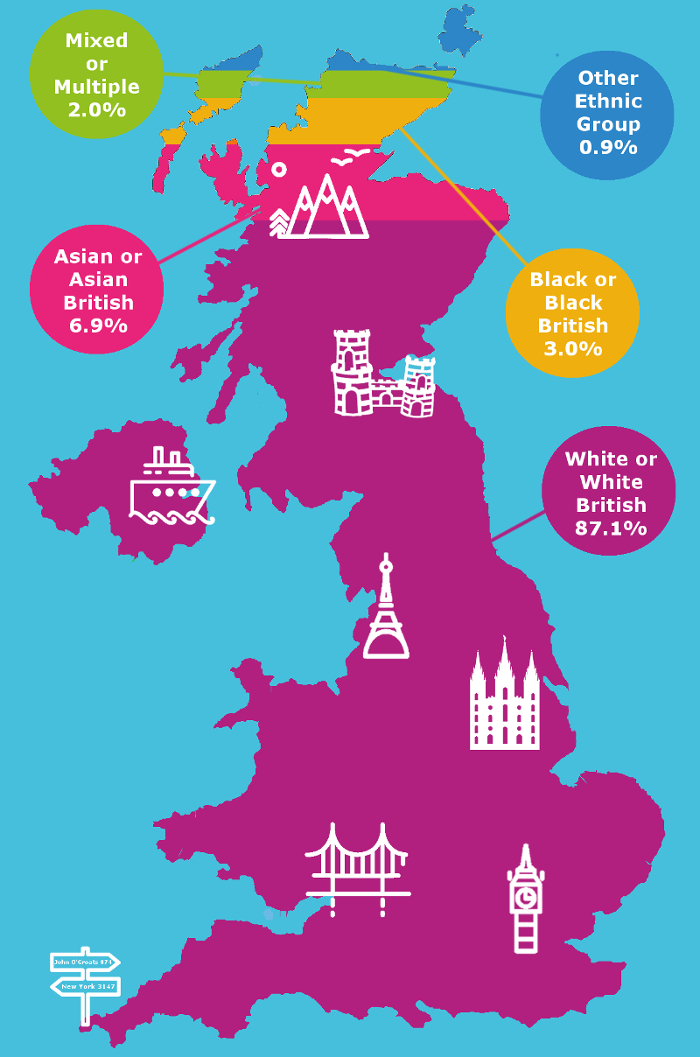

It's pretty hard to define race, and so the term 'ethnicity' is generally used by governments, businesses and public services. The UK government collects data about its population every 10 years in a record called a census. It was last performed in 2011. Take a look at what ethnic diversity in the UK was like then...

Ethnicity in the UK

This map shows the proportion of each ethnic group in the UK from the 2011 census. How do you think these numbers might have changed since 2011? Is it important that we collect data about ethnicity?

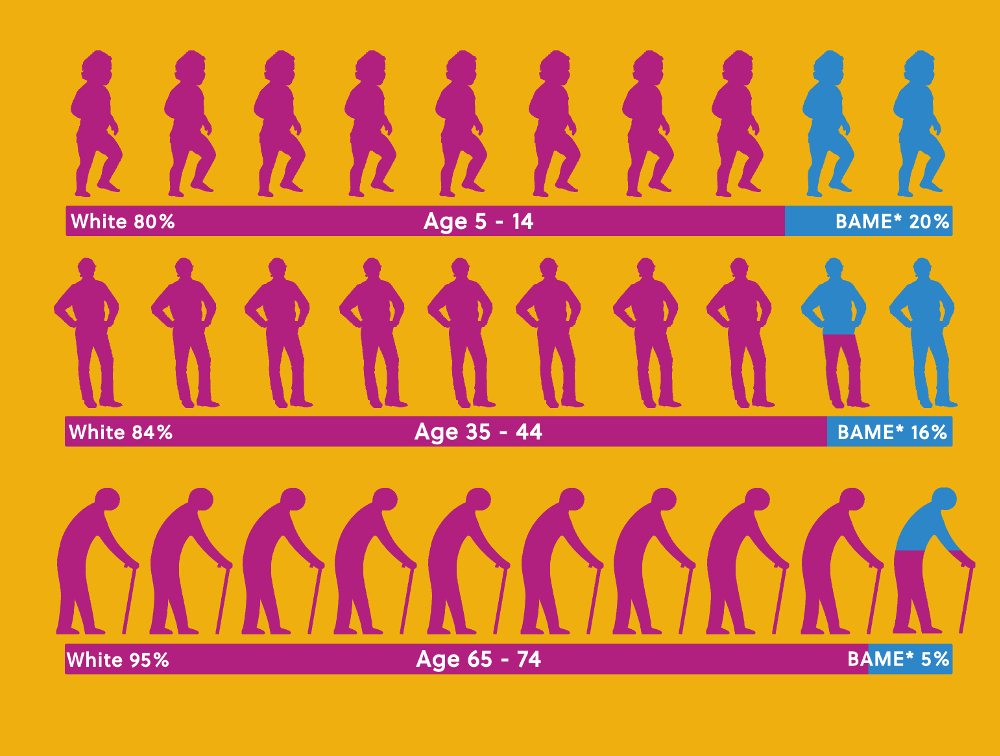

Ethnicity by age

This graphic shows the percentage of White and BAME (*Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) populations at different ages in the UK. There is more ethnic diversity amongst young people than amongst older people, why do you think this is?

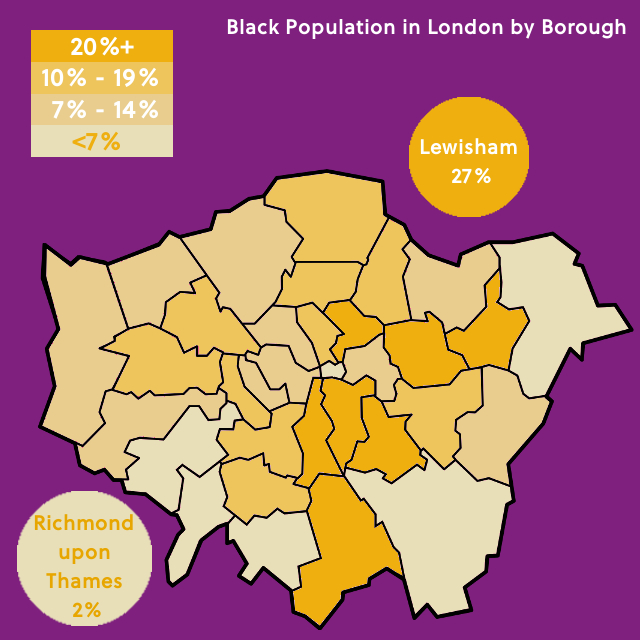

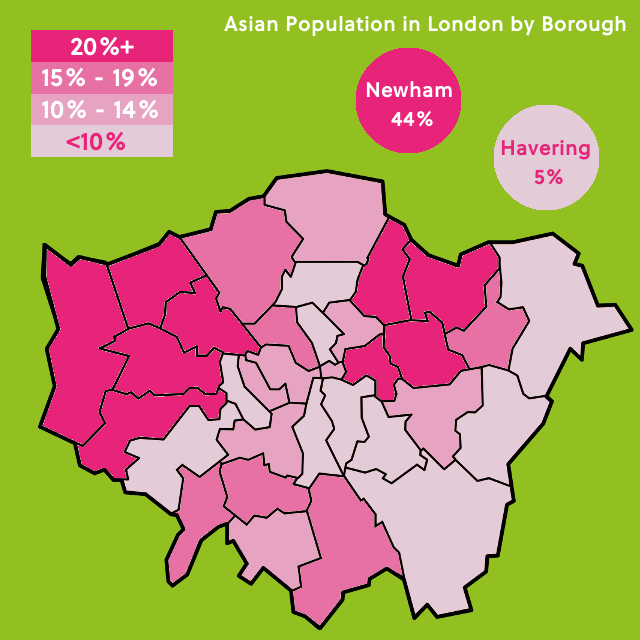

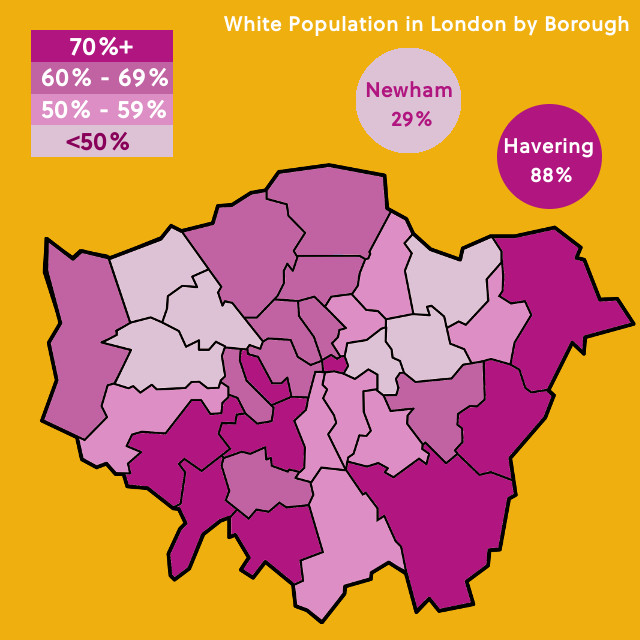

Ethnicity across London

These maps of London shows the percentage of Black, Asian and White populations in each of the London Boroughs. You can also see the Boroughs with the highest and lowest proportion of each ethnic population. How do you think these maps would have looked 50 years ago? How might they look in 50 years time?

Sources:

2011 census data - Office of National Statistics

2011 ethnicity by age - nomis official labour market statistics

2011 ethnicity by London Borough - London Datastore

Image: Blank map of London Borough (modified) Author: Richtom80 via English Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 2.5)

5 multiracial stories: through their eyes

-

'Still I Rise' by Maya Angelou

-

Maya Angelou (1928-2014) lived through times of terrible inequality for African American people. She was active in the Civil Rights Movement (which aimed to end racial segregation and discrimination) and worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Angelou wrote one of her most powerful poems, 'Still I Rise', in 1994. This poem directly addresses white oppressors of black people, which can be seen from her use of ‘You’ throughout. In the face of hatred, Angelou presents her determination to stand up for other black people, and her black ancestors. In this particular section of the poem, she tells society that no matter what they do to try to oppress her, they won't succeed:

"You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise."

-

-

'Theme for English B' by Langston Hughes

-

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was a poet and activist who joined and helped lead the Harlem Renaissance. This movement spanned from about 1918 until the mid-1930s and is often described as an explosion of literature, music, theatre, and the visual arts among African Americans in Harlem, New York City. Later in his life, in 1949, Hughes wrote 'Theme for English B'. This poem explores how a black student might (or might not) relate to his white teacher. The student in the poem is asked to write a page about himself, and the only instruction is to make this page ‘true’. The student questions the assignment, and its apparent simplicity, and asks if the ‘truth’ means the same thing to him as it does to his white teacher. In this section, Hughes wonders about the differences and similarities between black and white people, in both their lives and their writing.

"Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being colored doesn’t make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white."

-

-

'Americanah' by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

-

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie was born in Nigeria in 1977. Her 2013 novel, 'Americanah', tells the story of a teenage couple at a secondary school in Lagos (the largest city in Nigeria). At the time, Nigeria is under a military dictatorship (ruled by one person), and citizens are trying to leave the country. One of the teenagers, Ifemulu, travels to the USA to study, whilst the other, Obinze, goes to London. The two have opposing experiences during their time apart in two countries with very different histories. In American, Ifemulu struggles with her experiences of race and racism. Adichie (as Ifemulu) writes:

“The only reason you say that race was not an issue is because you wish it was not. We all wish it was not. But it’s a lie. I came from a country where race was not an issue; I did not think of myself as black and I only became black when I came to America. When you are black in America and you fall in love with a white person, race doesn’t matter when you’re alone together because it’s just you and your love. But the minute you step outside, race matters.”

Across the Atlantic, Obinze has very different encounters, faced with British politeness glossing over talk of race and a heavy focus on political correctness. Will they revive their relationship when they return to Nigeria?

-

-

'The Boy with the Topknot' by Sathnam Sanghera

-

Sathnam Sanghera was born to Punjabi parents in Wolverhampton in 1976. In this memoir, he writes about growing up as a second generation immigrant in the 80s, and his journey to studying at Cambridge University and gaining a highly-paid job as a newspaper journalist in London. The central thread of the story is Sanghera’s return to Wolverhampton in his 20s and his discovery that two of his family members have been struggling with mental health issues. In 2009, 'The Boy with the Topknot' was awarded Book of the Year by the charity MIND, which recognises books and authors that have raised awareness of mental health issues in their literary work. When he accepted the award, Sanghera said "there are hardly any books about Asian communities’ experiences of mental health problems, so I hope people read this book and it leads to more understanding.”

-

-

'The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian' by Sherman Alexie

-

Sherman Alexie grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Washington, USA. Alexie wrote this young adult novel from the perspective of a Native American teenager, known as “Junior”, exploring his life on the reservation and his decision to study at an all-white public high school (rather than the poor high school on his reservation). This experience introduces him to the differences between white culture and his own, particularly noticing how much stronger family ties are in his community. Throughout the school year, however, he also sees some of the darker sides of reservation culture as he loses family members to alcohol abuse. Junior relates in some way to both the Indian/Native American and American side of himself, but has difficulty establishing his individuality, as represented by this quote from the book:

“Life is a constant struggle between being an individual and being a member of the community.”

-