Since the birth of socialism, people have debated how “fair” it really is that some people are paid more than others. But how should we decide how much one worker should be paid compared to another? When is it fair to pay two people different wages? This requires further thought…

Would you pay|everyone the same?

Why are different jobs paid differently?

Two current Oxford students consider why people are paid differently for doing different types of work.

Nikita, who studies Philosophy, Politics and Economics, talks about some of the reasons why different occupations are paid at different rates, while History and French student Malaika discusses the case study of East and West Germany during the twentieth century.

In this video, Malaika discusses the impact of economic factors on people’s decisions to leave East Germany – but this is only part of a bigger picture! We asked History DPhil student Aleena Din to tell us more.

Aleena says: “There were complicated reasons as to why intellectuals made the dangerous decision to defect. The politics of East Berlin were characterised by the suppression of opposing and dissenting voices as a means to politically secure East Germany. This restricted the ability of professionals and intellectuals to work freely and without fear, which fed into people’s decisions to leave for Western countries. This ‘brain drain’, and the lack of professionals that it caused, fundamentally damaged the economic prospects of East Berlin. You can read more about this in books such as V.R. Berghahan’s Modern Germany: Society, Economy and Politics in the Twentieth Century.

Deserving success or just getting lucky?

Why don't rich people realise that they're rich? How much more should we pay people who work under difficult and dangerous conditions? And what's the role of luck in passing your exams?

Oxford University's Professor Danny Dorling and Oxplore intern Shona Galt discuss these questions and more...

What is Universal Basic Income?

Recently there’s been lots of talk about “universal basic income” as a suggestion for dealing with income inequality. But is it really a new idea? In this video, Vox Media’s Dylan Matthews looks at the history of guaranteed minimum income proposals and experiments in the USA way back in the 1970s and discusses some of the reasons why they didn’t go ahead.

Unconscious Bias, Discrimination and Salary: Six Sobering Studies

Many people today tend to say that they believe people who do the same jobs or perform the same roles should be paid equally. But does that always play out in reality?

Social scientists, psychologists and historians have conducted a range of studies suggesting that we’re not always as equal as we think we are when it comes to hiring workers and paying people for their work.

- Boys report getting more pocket money than girls

Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash - According to a report published by market research agency Childwise in 2017, boys reported receiving more pocket money than girls – boys aged 5-16 reported receiving an average of £10.70 per week from either pocket money, payment for chores or paid work, while girls of the same age received £8.50.

- The gap was particularly large for children aged 11-16, when boys reported receiving £17.80 and girls £12.50.

- Be aware: There are some caveats to this study - one is that the levels of pocket money were self-reported by children using an online survey: parents weren’t asked about how much pocket money they gave out!

- Another issue is that the survey also found that girls' pocket money was more likely to be 'topped up' by parents buying them additional expensive items such as clothes and makeup. Childwise's research manager Jenny Ehren, speaking to The Guardian, comments that “The value of these purchases almost certainly helps to bridge the income gap between boys and girls... but the approach to managing finances is noticeably different... [as] boys are more likely to be entrusted with regular cash payments, while girls are more reliant on other people buying them items, or managing money on their behalf". This may deprive girls of the opportunity to learn money management skills and build independence. Read more.

- Employers would offer “John” more money than “Jennifer”…

- Researchers at Yale University created a fictional CV for an imaginary student, and sent copies of it to science professors at top research universities around the USA. They asked the professors to rate how competent they thought the student was, how likely they would be to hire or mentor them, and how much they would be willing to offer them as a starting salary as an employee.

- The twist was that 50% of the CVs were sent out with the name “John” at the top, and 50% with “Jennifer”. The study found that despite the CVs being identical, the professors rated “John” as more competent, and said they were more likely to hire and mentor him. They also said that they would offer “John” an average starting salary of $30,283.10, while CVs attributed to “Jennifer” were offered an average starting salary of $26,507.94. Starting salaries are important, especially in a person's first job, because they can have an impact on the person's ability to negotiate pay rises in the future. Read more

- … and they’re more likely to hire “Emily” and “Greg” than “Lakisha” and “Jamal”.

- A famous 2003 study from the US National Bureau of Economic Research sent out responses to job advertisements in Chicago and Boston using CVs with either stereotypically “white”-sounding names or stereotypically “African-American” names. They found that CVs sent out with the “white names” received about 1 callback for every 10 applications, while those with African-American sounding names received 1 callback for every 15 applications.

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- They also found that higher-quality CVs increased the likelihood of being called to interview for applications with “white names”, but having a high-quality CV made much less difference for applications under “African-American names”. Read more

- Recently, the BBC ran a similar test with a CV attributed to either “Mohamed Allam” or “Adam Henton”. It found that employers in the field of business management were less likely to offer “Mohamed” an interview, and recruiters were less likely to contact him on a job-seeking site. Read more

- Women are judged more harshly when they ask for more money

- It’s been suggested that one reason women may receive lower salaries is because they are “less assertive” and less likely to negotiate for a pay rise. So women should just learn to ask for more money, right?

- Not so fast. Researchers at Harvard University have found that one reason women are paid less could be because people react more negatively to women who try to negotiate for higher pay. In the study, a group of people were asked to read about or watch a video of an imaginary job candidate. The candidate was shown either accepting a salary offer or asking for more money. The researchers then asked people

- A) Whether they would be willing to hire that person as an intern, and

- B) How willing they would be to work with that person as a colleague.

- The study found that people were less willing to hire both male and female interns who asked for more money - however, the negative effect of negotiating was more than two times greater for female interns than it was for male interns.

- It also found that people were no less willing to work alongside a male candidate who attempted negotiations. However, they said they were 5.5 times less willing to work alongside women who negotiated, perceiving them as "too demanding" and "not nice".

- There were also some differences between people's responses to written documents and video: when participants viewed video of the candidates negotiating, male evaluators penalised female candidates more than male candidates for asking for more money while female evaluators penalised all candidates who asked for more. Read more

- As more women enter a profession, it tends to become less well-paid

- Another major factor in the gender pay gap is that women tend to work in fields that are lower-paid. So maybe they should just choose better-paying jobs? Again, it's more complicated: a historical study from researchers Asaf Levanon, Paula England, and Paul Allison looking at census data from 1950-2000 showed that as women started moving into the workforce, jobs that attracted a greater proportion of female workers began to be less valued than they had been when mostly men were performing the work – even after controlling for factors such as education, skills, geography and ethnicity. For example, during the period studied wages for biologists fell by 18 percentage points as the field became more female-dominated.

- The opposite can happen too -- while wages for computer programmers were low in the 1940s when programming was seen as “women's work”, pay in the industry rose as more men entered it in the 1960s and 70s. Read more

- US Navy Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, working on the UNIVAC computer in 1960, at a time when computing was seen as a more suitable profession for women. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

- Male eBay sellers receive higher bids on identical items

- Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash

- Wait a minute, can you even tell the gender of a seller on eBay? Sociologist Tamar Kricheli-Katz and economist Tali Regev set out to find out. They established that around 56% of the time eBay users can guess the gender of sellers through clues such as usernames and "other items for sale" listings.

- Kricheli-Katz and Regev also looked at 1.1 million eBay transactions around the world between 2009 and 2012, and found that for identical new items such as iPods and gift cards, women received only 80 cents in the dollar in bids. Their research suggests that some of the difference might be due to men and women using different language to describe their goods, but some of the difference is still unexplained. Read more

Made in Dagenham:|The Fight for Equal Pay

'Made in Dagenham' is a musical adaptation of the 2010 film of the same name. It's based on the real-life strike action of the sewing machinists of the Ford factory in Dagenham in 1968. Meet the current Oxford students who are performing in 'Made in Dagenham', and hear their views on the workers' struggles to win equal pay...

The links that Olivia mentions are:

Video featuring real Dagenham workers' stories of the strike

Made in Dagenham:The History Behind the Musical

The Walk Out…

In 1968, it was commonplace for women to be paid less than men irrespective of the skills involved in the work. This was the case for sewing machinists working for Ford Motor Company, who were regraded within the company’s pay structure from Category C -- meaning skilled production jobs -- to Category B, meaning less skilled production jobs.

When this happened, the women discovered that they would be paid 15% less than men in Category B jobs. Outraged that they were being paid less than male workers, on the 7th June 1968 one hundred and eighty-seven machinists at the Ford Dagenham plant walked out on strike. They were led by a group of five women: Rosa Boland, Eileen Pullen, Vera Sime, Gwen Davis, and Shelia Douglass.

It wasn’t long before other machinists at Ford's Halewood Body & Assembly plant followed, causing car production to come to a complete halt.

A Day at Whitehall….

With large amounts of the production at a standstill, the UK managing director of Ford laid off 9,000 workers at Dagenham who were eventually reinstated, with a further 40,000 jobs at risk. It is estimated that the strike cost the company export orders worth around £117 million today. The strike had to end so on the 28 June 1968, several of the machinists travelled to Whitehall to try and fight for equal pay. It was on this day that eight of the strike leaders met with Barbara Castle, the Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity in Harold Wilson's government, and forged a deal that would end the three-week strike. The machinists pay was instantly increased to 8% below that of the men and was raised to full Category B pay rate the following year. Unfortunately, it took a further six-week strike in 1984 to be regarded as Category C workers.

A Big Impact…

The 1964 Labour manifesto pledge ‘the right to equal pay for equal work’ had amounted to nothing and the issue had been forgotten. The Dagenham strikers inspired further strikes by women trade unionists and the National Joint Action Campaign Committee for Women's Equal Rights (NJACCWER). On the 18th May 1969, an equal pay demonstration was attended by over one thousand people in Trafalgar Square. To prevent further protesting, Barbara Castle then decided to put in force the Equal Pay Act (1970): An Act to prevent discrimination, as regards terms and conditions of employment, between men and women. The actions of the Dagenham machinists that summer triggered a nationwide debate about equal pay that is still going on today.

The Equal Pay Act that the Dagenham machinists triggered is a landmark in the fight for women’s rights in politics. It is also an example of how protest movements can lead to changes in the law and policy of a country.

Take this further:

Here are some of Olivia's suggestions for further thinking and research:

History: How important was the Dagenham strike in gaining equal pay for women?

• Research and place the strike in the context of wider changes in the period such as feminism and other rights movements

• Make a timeline of the events at Dagenham alongside the Labour pledge and the National Joint Action Campaign Committee for Women's Equal Rights (NJACCWER) action

• These websites might help:

http://www.striking-women.org/module/workplace-issues-past-and-present/gender-pay-gap-and-struggle-equal-pay

Politics: Do we have equal pay?

• Think about different careers and whether these are equal such as in the film and television industry, sports, engineering etc.

• Research equal pay around the world, does every country have the same type of legislation that we do?

• These websites might help:

http://uk.businessinsider.com/countries-with-the-biggest-gender-pay-gaps-2017-10

You might also be interested in another Oxplore Big Question: Should Footballers Earn More Than Nurses?

Bonus:

Have a look at what some of the actual Dagenham strikers had to say about their experience: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/jun/06/dagenham-sewing-machinists-strike

Did you know...

... that there's even a gender pay gap in tennis? According to the New York Times, in 2015 the winner of the men’s Western & Southern Open competition, Roger Federer, received $741,000 in prize money while the winner of the women’s competition, Serena Williams, received $495,000 – just 66.8% of the men’s prize.

What about childcare?

As well as working for money, many people do unpaid labour in the form of childcare, housework, caring for elderly relatives or other responsibilities. How does this impact their income and ability to earn money? Sarah Kliff from Vox Media explores the research:

Globalisation and the gender pay gap

If a company does business internationally, does that make it more or less likely to have a gender pay gap? Recent research from Imperial College London, the University of Oxford and the University of Oslo shows that if a company works across multiple time zones, it’s actually less likely to pay men and women the same. Professor Esther Bøler explains…

Companies that do business across multiple time zones have a greater gap in pay between men and women than companies that don’t.

The gender wage gap persists across the globe, even if the latest news from the UK Office for National Statistics is uplifting. The most commonly cited reasons include differences in working hours, life-time labour-force experience, occupational choices, college majors, and fewer women receiving promotions to higher level (and therefore higher paying) positions.

While the glass ceiling, the salaries for the types of jobs men and women typically hold, and differences in hours worked are all significant contributors to the gender wage gap, there are less obvious factors that also play a part. Whether or not a business works across multiple time zones is one.

My recently published research, undertaken alongside my colleagues Beata Javorcik from the University of Oxford and Karen Helene Ulltveit-Moe from the University of Oslo, examines differences in the gender wage gap between companies that do business with international partners, and those that don’t.

Women are perceived as being more family orientated than men, and are subsequently less reliable and less committed to their job

Our research specifically looked at the manufacturing sector in Norway, a country with a large amount of information available regarding a person’s pay, and a relatively narrow gender wage gap. Norway’s high ranking in terms of labour market efficiency by the World Economic Forum also makes it an excellent research candidate.

Our research ultimately found that, among college graduates, exporting firms have about a three percentage point larger gender wage gap than non-exporters. While women tend to earn a greater income at a business that operates across borders, they are ultimately being undervalued in comparison to their male colleagues.

Never out of the office

We can attribute this greater gender wage gap to the demands of the modern, international workplace and the challenges that go with working across time zones. Employees doing business internationally have far greater demands made of their time: a manager might need to take a telephone call at two am from a client in Australia, fly to their US partner’s office at a moment’s notice, or work weekends in order to overcome a customs delay for an important delivery.

The less time zone overlap a company has with the destination of its exports, the greater the gender wage gap

Technology has also increased the pressure on an employee’s schedule: laptops, smartphones and tablets have transformed anywhere with a power plug and an internet connection into a remote office, and employees are expected to make full use of these tools to respond to issues immediately.

In a globally competitive market, this has all made employee flexibility extremely valuable to companies doing business with global partners.

This accelerated pace of work and the increased value placed on being flexible has ultimately meant that if someone is inflexible, or is perceived as such, they lose out in terms of wages. Employer surveys frequently report women are perceived as being more family orientated than men, and are subsequently less reliable and less committed to their job. While this perception may or may not be correct, it is having a very real effect on women’s earnings.

For non-exporters, being available around the clock is far less important. Workers might have to work late or early on occasion, but if the majority of their business is conducted locally, their business partners are operating on the same schedule they are. Flexibility is far less valuable, and subsequently women are penalised less at these types of companies.

Time and tide wait for no woman

We have confirmed this by breaking down the salary data in several different ways.

Our research found that working across multiple time zones has a greater effect on the gender wage gap for people aged under 45. Women in this age group are more likely to have young children, potentially limiting their ability to work flexibly.

The gender wage gap is also affected by the number of time zones a company operates across. The less time zone overlap a company has with the destination of its exports, the greater the gender wage gap. As the percentage of a company’s output that it exports increases, so does the gender wage gap. The gap is also larger at companies that export to a greater number of markets, and also at companies that export a greater variety of products.

Exporting firms have about a three percentage point larger gender wage gap than non-exporters

Ultimately, all these results can be explained by export companies valuing the flexibility needed to do business across multiple time zones, and those companies placing less trust in women’s ability to do this type of work.

The gender wage gap surfaces in unexpected and complex ways, and closing the gap should not completely come down to broad measures to address inequality – in particular across whole sectors or industries. Companies will have to take a careful look at their particular operations in order to address their own specific inequalities.

This article was originally posted on the Imperial College London Business School blog. Click here to read the original post.

Is the gender pay gap a good way to measure inequality?

It's not OK to discriminate against people -- but are measures such as the gender pay gap always the best way to find out whether discrimination is taking place? Dr Maja Založnik from Oxford University's Institute of Population Ageing explains how simply focusing on the gender pay gap could cause policymakers to miss the bigger picture -- or even lead to employers gaming the system.

What about ethnicity?

Several recent studies have shown that there are also pay gaps by ethnicity in many industries. At the time this Big Question was written, the government was considering whether there should be mandatory reporting on ethnicity pay gaps in the same way that there is now compulsory gender pay gap reporting. What are the pros and cons?

In 2017, the UK introduced mandatory gender pay gap reporting, meaning that all employers with more than 250 staff members are now required by law to publish information about gender disparities in rates of pay and bonuses.

The results are collected and published on a website run by the UK government, which has allowed people to get a better idea of where pay gaps are and which companies need to improve.

But what about pay gaps between workers from BAME (Black and minority ethnic) backgrounds and white workers?

In 2018, an audit of pay rates for public sector workers in the City of London found varying pay gaps – for example, while London Fire Brigade employees of all races were paid the same, BAME employees at the Metropolitan Police were paid 16.7% less than white officers, while the Old Oak and Park Royal development corporation (a development group working in West London) had a 37.5% pay gap. Read more

Meanwhile in the university sector, a 2018 report found that black and Asian staff are significantly more likely to work in lower pay grades and less likely to be appointed to more senior roles. Read more

Why is this?

As with the gender pay gap, there are lots of complex interacting factors: people might have different qualifications, apply for different jobs, or take different career paths as well as coming from different ethnic backgrounds. It’s difficult to get a really complete picture at the moment, as various reports have been compiled for different employers and industries. Broad details about household incomes and participation in the labour force were gathered in the UK Government’s 2017 Race Disparity Audit, but there isn’t a complete overall set of statistics on pay gaps by ethnicity.

At the time this Big Question was written, the government was considering whether there should be mandatory reporting on pay gaps by ethnicity in the same way that there is now compulsory gender pay gap reporting.

For and against

Some people have raised concerns about this – for example, Len Shackleton of the Institute of Economic Affairs, a right-wing lobbying group, argues that small numbers of individuals in small firms will lead to statistically insignificant results, while Jim Pickard, writing for The Financial Times, points out that the Office for National Statistics uses 18 standardised ethnic classifications, which will be a lot of detail to manage and report. Read more

On the other hand, commenters such as Shafi Musaddique, writing for The Independent, argue that mandatory reporting will increase incentives for employers to ensure fairness and commit to diversity in the workplace. Read more

What do you think – should there be mandatory reporting for ethnicity pay gaps?

Is income inequality inevitable?

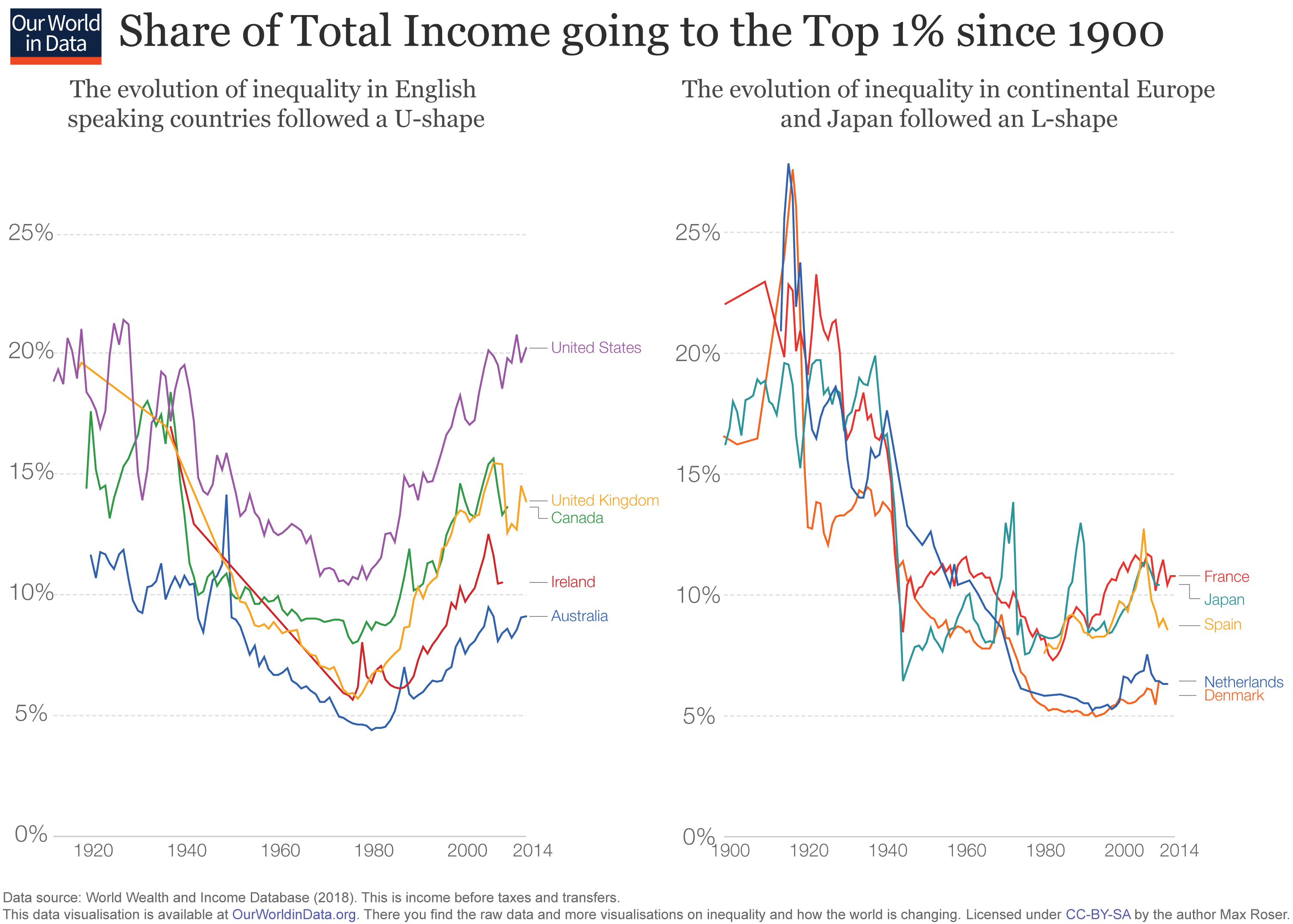

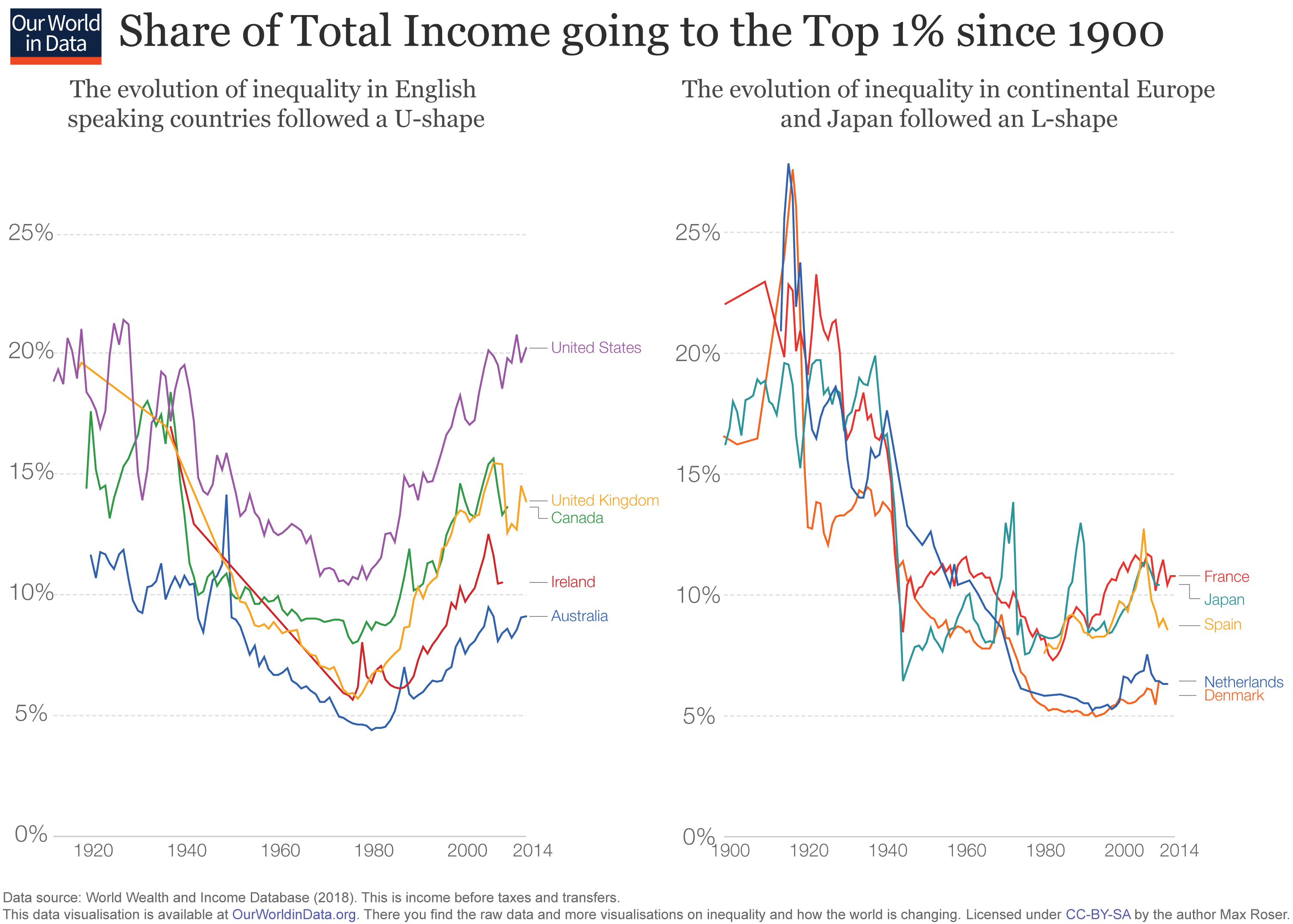

You might have already come across the idea of “the 1%” – the top 1% of the population in terms of income. Researchers looked at ten different countries to see how large “the 1%”’s share of total annual incomes really were, and found some major differences between English-speaking and European countries.

Broadly speaking, “the 1%” tends to refer to the top 1% of the population in terms of either income or ownership of assets. The amount of wealth and property controlled by “the 1%” is often seen as a measure of how equal, or unequal, a society tends to be.

Researchers at the University of Oxford’s Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development used tax records from throughout the twentieth century to look at the income of “the 1%” and compare it to the total national income over time.

View the original graph on the Our World in Data website

In the left-hand graph, check out income distribution in the USA (the purple line). In the early twentieth century, around 20% of the nation’s income was controlled by the richest 1%. This dropped to between around 10% and 15% from the early 1950s until the mid-1980s (with a low point of around 11-12% in the 1970s). From the 1980s, the richest 1%’s share began to climb again, and by 2014 it was back to the same level that it had been in 1920.

This income distribution pattern follows a U-shape. It starts with a relatively large share going to “the 1%” in the early twentieth century, then moves to a more even distribution of income in the late twentieth century. It then goes back to a more unequal distribution of income in the twenty-first century. Similar patterns are followed in the UK, Canada, Ireland and Australia.

What do you think: Can you think of any major historical events or political movements that took effect in the 1940s and the 1980s? How might these have impacted the distribution of income in English-speaking countries?

Meanwhile, in the right-hand graph we can see the income distribution of several European countries plus Japan. They all follow an L-shape: starting out with a high share of income going to the 1%, falling abruptly and then stabilising over time.

Let’s focus on the Netherlands (the dark blue line) as an example. In 1920, its richest 1% received an even greater share of the income than the USA’s: over 25% of the total national income. Similarly to the USA, the Netherlands 1%’s share dropped in the 1940s and 1950s – but unlike the USA, it did not rise in the 1980s but continued to fall: in 2014 the richest 1% of the Netherlands were getting just over 5% of the national income.

What do you think: What do you know about life in the Netherlands and Denmark? What differences are there between these countries and the USA, and how might these account for differences in the share of income going to “the 1%”?

Professor Max Roser comments:

“A lesson that that we can take away from this empirical research is that political forces at work on the national level are likely important for how incomes are distributed. A universal trend of increasing inequality would be in line with the notion that inequality is determined by global market forces and technological progress. The reality of different inequality trends within countries suggests that the institutional and political frameworks in different countries also play a role in shaping inequality of incomes. This means that rising inequality is most likely not inevitable.”

This article was adapted from an article written by Professor Max Roser. You can read the full article, with more graphs and information, on the Our World in Data website.

Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2018) - "Income Inequality". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/income-inequality' [Online Resource]

How does globalisation affect income worldwide?

Free trade and globalization spread opportunities to do business to workers in developing countries. However, one result of this is that work tends to move to areas where labour costs are lower and regulations on the way workers can be treated are looser. How does this affect people's quality of life around the world?

Free trade and globalization spread opportunities to do business around the world. However, one result of this is that work tends to move to areas where labour costs are lower and regulations on the way workers can be treated are looser. This can lead to job losses in some parts of the world, and opportunities for exploitation and unsafe working conditions in others. In this video, the team from Crash Course Economics explain the effects that global free trade has had on people's ability to work and earn money.

.

Are boycotts the answer to global inequality?

In 2013, a terrible accident at a garment factory in Bangladesh sparked outrage around the world. Many people in countries such as the UK and the USA proposed boycotting fashion brands that use international factories with unfair or unsafe working conditions. But does refusing to buy goods protect workers’ rights, or just take away their livelihoods? Professor Brooke Ackerly from Vanderbilt University explores the issue...

Five years ago, on April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh collapsed killing 1,134 garment factory workers inside. Just five months before this accident, a fire at the Tazreen Fashion factory killed 112 people.

The disasters left many Americans wondering how to respond to prevent such tragedies from happening again. The companies whose brands were manufactured at these factories and other global garment retailers wondered how to keep their customers in the face of worldwide condemnation of Bangaldesh factory working conditions.

Almost immediately, even with no known association with Rana Plaza factories, the clothing company PVH (maker of Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger and other brands) signed the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a five-year, legally binding agreement among international brands and retailers, Bangladeshi trade unions, and international trade unions to work together to improve factory conditions, created in May 2013.

The Walt Disney Company took another approach; it pulled its production from Bangladesh, effectively boycotting the country.

Which strategy is better for Bangladeshi workers? And which strategy should consumers support?

To answer these questions, we must ask two more. What approach would empower the more than 4.2 million Bangladeshi garment workers? And what approach would hold brands accountable? These are the keys to better working conditions long-term.

Studying the lived experience of labor activism

In 1993 a group of village women in Bangladesh introduced me [Professor Brooke Ackerly] to their strategies for social criticism.

In my view, political theory about ethics and responsibility should be informed by the lived experience of those in the struggle.

Since 2010, I have been studying labor, environment, and gender justice as these have been pursued by activist organizations. The argument below draws on the insights from the grass roots of the global labor movement.

A simple boycott of Bangladeshi manufacturing is not accountable to the workers.

A boycott is not a just approach to labor injustice because, if successful, it would leave the workers without their source of livelihood. To understand what justice requires and what it means to respect the human rights of workers in struggle for their rights, we need to understand what they mean by their “rights,” for example by listening as Kalpona Akter, an activist and a former child worker in the Bangladesh garment industry, addressing the 2013 Wal-Mart shareholder meeting in the video below.

‘Boycotting is suicide for my country’

Boycotting, whether by brands or consumers, may indeed send a message to clothing companies, the Bangladeshi garment industry, and to the government of Bangladesh that poor working conditions are unacceptable.

But that message may cost workers their livelihood. As Kalpona Akter, who is with the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, once said to my Vanderbilt University students, “a boycott is suicide for my country.”

Instead, consumers may be more effective by giving political support to Bangladeshi workers who are trying to change the practices of garment factories and retailers. They may use social media to organize and to protest at stores. In each example they are not merely consumers. They are acting politically and ethically to support workers.

US consumers have been encouraging corporations to sign the Accord on Fire and Building Safety.

Students from universities across the US, including Rutgers and NYU, have urged their schools not to source school spirit garments from VF Corporation, owner of the Jansport brand, until VF signs the Accord. Two hundred brands have done so, including Abercrombie & Fitch, American Eagle Outfitters and Fruit of the Loom.

So why did a company like PVH know how to respond with accountability? Because company representatives had already been talking with workers.

After the That’s It Sportswear factory fire killed 29 workers in Bangladesh on December 14, 2010, labor groups, PVH and other US brands began negotiating on factory safety. Then, in March 2012, after ABC News confronted Tommy Hilfiger at Fashion Week with news that workers had died sewing his clothing, PVH signed an agreement on factory safety. After Rana Plaza, that agreement was modified, updated, and went into effect under its current name, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. In other words, PVH management had been listening to workers and understood that accountability to workers was the key to an effective solution.

Another way companies can be accountable to workers is by contributing to the Rana Plaza Donors Trust that helps compensate the over 5,000 survivors and victims’ families, many of whom were orphaned.

To encourage corporations to pay their share to the Rana Plaza Donors Trust, students and consumers have been delivering letters to store managers of clothing retailers including The Children’s Place and the Italian company Benetton. On Friday, April 24, a press release from Workers United-SEIU, announced that an agreement had been reached in which The Children’s Place would contribute an additional $2 million to the Rana Plaza Donors Fund.

These students and consumers are working in partnership with labor rights groups, unions, anti-sweatshop groups, and Bangladeshi activists to bring political attention to worker rights.

Two of these activists are Kalpona Akter from the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity(BCWS) and Mahinur Begum, who was 16 when Rana Plaza collapsed around her. Ms Akter founded BCWS in 2001 with two other former garment workers who had been part of an earlier effort in the 1990s to form a trade union in a garment factory in Bangladesh. The AFL-CIO’s Solidarity Center conducted the training: “The Solidarity Center supports a mission to help build a global labor movement by strengthening the economic and political power of workers around the world through effective, independent, and democratic unions.”

The BCWS was originally founded as a non-government organization promoting worker organizing in sectors other than the garment sector. However, the needs of organizing workers for legal defense and the need for workers in non-union factories for arbitration with their management has kept BCWS focused on the garment industry.

Through their work in legal awareness training for workers, code of conduct training for workers and factory managers, leadership training for worker leaders, and advocacy, BCWS activists have earned the respect of both workers and managers for their skills in conflict resolution.

Yet organizing in Bangladesh can be dangerous.

Even in the US activism is not without some risk. On March 12 this year, Kalpona Akter, Mahinur Begum and two dozen others were arrested at the Secaucus, NJ, headquarters of Children’s Place for trespassing when they tried to deliver a written request for increased compensation to the Rana Plaza Trust. The charges against the Bangladeshi activists and the students in the group were later dismissed.

Trust fund lacks support from key players

Today the trust still has not received adequate donations to meet its obligations.

Although some companies whose clothing was produced at Rana Plaza – like Cato Fashions and JC Penney – have given nothing at all, others companies such as Benetton have contributed, though less than advocates have called on them to give.

Three companies (H&M, Gap and N Brown Group) have donated to the trust even though they have no known association with Rana Plaza factories. Like those who have signed the Accord, they want their consumers to perceive that they are on the right side of this issue.

Both the Rana Plaza Trust and the Accord on Fire and Building Safety are important ways to be accountable to workers. Even with these achievements, however, long-term improvement in working conditions will require effective advocacy within Bangladesh.

For that to happen it has to be safe to speak up. “Bangladesh has a history of corruption, of political turbulence,” Ellen O. Tauscher, a Californian politician who is chairwoman of the of the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, told the New York Times.

Non-boycott consumer activism has helped on this front, too.

For instance, in 2010 an international letter-writing campaign coordinated with local organizations secured the release of worker rights activists who had been arrested and heldon false charges.

Non-boycott activism has also helped secure better working conditions in many factories as well as the payment of back wages for many workers.

Though workers still experience retaliation for speaking out about factory conditions and for organizing, they have been able to form unions recognized by the government and their work places. And the minimum wage has increased.

The work environment in Bangladesh is being transformed.

Taking steps to accountability

Taking responsibility for worker rights means being accountable to the workers who make the clothes brands sell and consumers wear.

Through basic economics of supply and demand, our choices as consumers affect others. Raising awareness of this fact can be done in small steps – by asking the managers at the stores where we shop about the working conditions under which the clothes we can afford and choose to wear are made.

The consumer today is not alone. There are many ways to nudge brands to support humane working conditions and accountability.

Social media connections with organizations like Clean Clothes Campaign and the International Labor Rights Forum can help consumers identify brands that are concerned with labor rights. Social media also enables consumers to signal to each other and to brands that they care about social responsibility. The power to change work places is not merely a purchasing power.

Our greatest contribution would be to ensure that another Rana Plaza collapse doesn’t happen and that working conditions continue to improve for all workers.

April 24, is the Global Day of Action: Remembering Rana Plaza. We must not let this disaster be forgotten.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. Click here to read it in the original.

What do you think: Is it enough simply to donate money to support victims? For example, fashion company Benetton gave $US1.1 million to the Rana Plaza Trust under pressure from consumers -- but this represented less than 0.07% of their annual turnover of $US1.6 billion. Will this discourage future companies from using unsafe factories, or could a similar tragedy happen again?

Would you pay everyone the same?

-

People earn different amounts of money for all sorts of reasons

It’s difficult to say that everyone deserves the same wages when they might be working in jobs that have different barriers to entry, require very different types of skills, or provide different levels of fulfilment. Some people have proposed universal basic income – a system whereby everyone gets a minimal amount of money to live on and then works for extra payment – as a way of combatting poverty and inequality. But this might discourage people from doing difficult or unpleasant jobs or undertaking demanding training such as that required to become a doctor or a scientist. In some cases, such as in East Germany in the 20th century, policies intended to create equality might even make people want to leave the country.

-

Differences in people’s incomes could be down to luck

Is it fair for some people to have so much more than others when the differences between people’s incomes could be down to luck? Professor Danny Dorling argues that we don’t realise how much of our good fortune – or bad fortune – might be down to chance as well as hard work, and that many wealthy people don’t realise how lucky they are.

-

Unconscious biases might affect people’s opportunities

We might say that two people who do the same work should be paid the same wages – but the proof isn’t always in the paycheques. Studies from economists, sociologists and psychologists show that when hiring and salary decisions are being made, women and people from ethnic minorities are missing out on money and opportunities. What could we do to make this fairer?

-

Childcare and other unpaid labour has a big impact too

Childcare and other unpaid labour – such as looking after elderly relatives and house work – also affects people’s earnings throughout their lives. Studies show that women who have children have larger pay gaps than women who don’t, and that this problem is more serious in the business sector than in the science or tech fields. Businesses working internationally across different time zones may also contribute to this issue as people need to be available at longer or more anti-social hours.

-

Pay gaps might not tell the full story

While the existence of pay gaps around gender or ethnicity might indicate that discrimination is taking place, Dr Maja Založnik points out that they are also linked to wider social factors which can be very complex. She also argues that focusing on pay gaps as a target might lead to companies trying to 'game the system' in ways that are damaging to people from marginalised groups.

-

The amount of wealth controlled by “the 1%” varies across different places and times

There will probably always be a “top 1%” of the population in terms of income – it would be very difficult to ensure that everyone was exactly equal at all times. But historical tax records show that the total income controlled by “the 1%” can vary a lot. For example, in the Netherlands in the 1920s, the richest 1% received nearly 30% of the total income of the country – but by 2014 their share had fallen to just over 5%, meaning that the remainder of the income could be distributed more equally

-

Globalisation can lead to low incomes and unsafe working conditions

When companies are able to trade and manufacture around the world, they will tend to move their manufacturing to wherever labour costs are lowest. This often goes hand-in-hand with looser regulations on health and safety, meaning that workers in poorer countries might receive wages and work under conditions that would be unacceptable in countries such as the UK and USA, while workers in developed countries might see their jobs move overseas.

-

But it can also lift people out of poverty

However, global manufacturing also provides people with opportunities to earn money that they might not otherwise be able to access, and supports the economy of developing countries such as Bangladesh. Workers such as Kalpona Akter argue that “boycotting is suicide” for their countries, and that we should instead support workers in their fight to attain safer working conditions and better wages while continuing to work in these industries.